Executive Summary

In an era where digital innovation drives global economies, the intricate world of semiconductors has become a new frontier for geopolitical conflict. Taiwan, a small island nation, stands at the epicenter of this struggle, holding a dominant position in the manufacturing of advanced microchips that power everything from our smartphones to military hardware.

Recently, a Chinese state-sponsored threat actor escalated spear-phishing campaigns specifically targeting the Taiwan’s semiconductor industry. The objective appears to be supporting China’s efforts to achieve semiconductor self-sufficiency and reduce dependence on international technologies and supply chains, particularly in response to export controls imposed by the United States and Taiwan.

Technical Detail

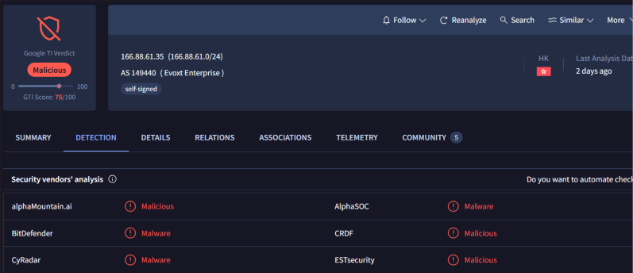

During the investigation, Proofpoint identified a Cobalt Strike beacon communicating with an IP address 166.88.61[.]35 previously associated with attacks on more than 70 organizations worldwide. By tracing the infrastructure leveraged by this Chinese threat actor, investigators aim to broaden the scope of the inquiry and uncover additional related components.

The IP address in question has previously been flagged as malicious by multiple security vendors on VirusTotal, as illustrated below.

Fig.1: IP is tagged as malicious in VirusTotal

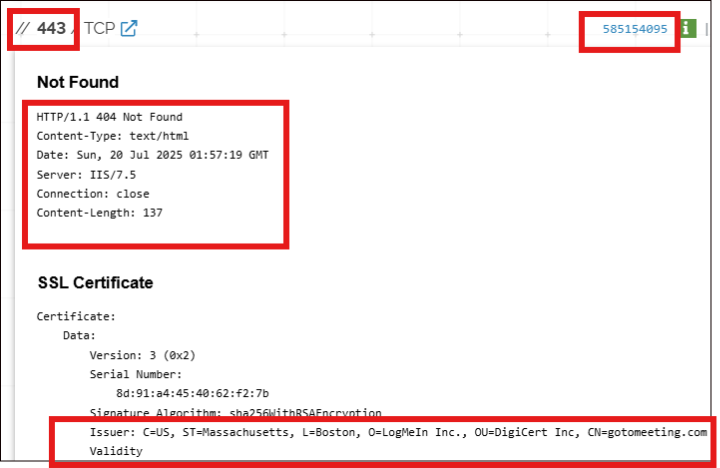

By querying the IP address on Shodan and analysing the host banner on port 443—commonly associated with Cobalt Strike command-and-control (C2) servers—we can identify pivot points that provide further insight into the threat actor’s infrastructure and support broader mapping

efforts.

Fig.2: Banner response of IP

Below is the response banner observed when connecting to port 443:

HTTP/1.1 404 Not Found

Content-Type: text/html

Server: IIS/7.5

Connection: close

Content-Length: 137

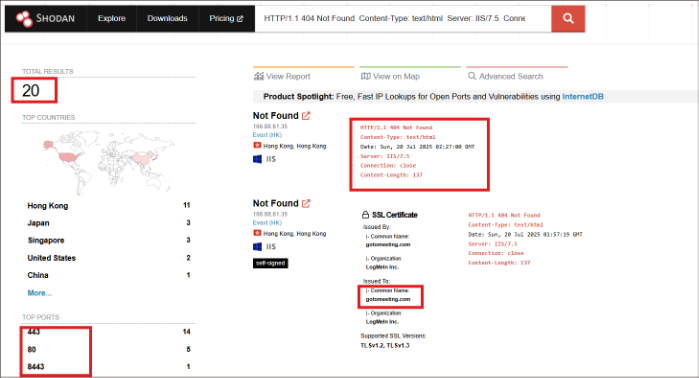

From this analysis, we can observe distinct characteristics and patterns that can be leveraged to proactively hunt related infrastructure. By pivoting on the host banner response, I have identified approximately 20 additional IP addresses potentially linked to the same threat activity.

Fig.3: Result of querying the banner response

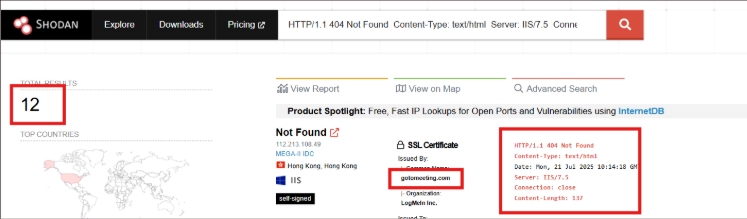

By pivoting using the above Shodan query, we were able to identify approximately 12 IP addresses potentially associated with the threat infrastructure on port 443.

Fig.4: Result of querying the banner response on port 443

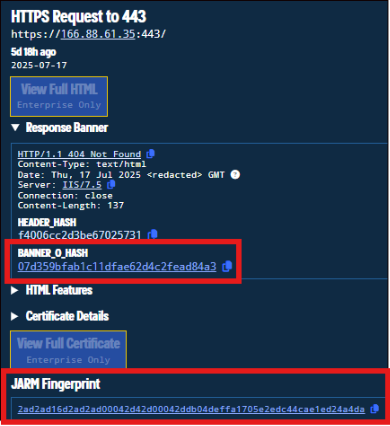

To identify servers that are now offline-likely due to the threat actors rotating or relocating their infrastructure—we will leverage the Validin platform, which is better suited for retrieving and analyzing historical data.

Fig.5: Banner response of IP in Validin

From the above figure we found new pivoting points to hunt the infrastructure like

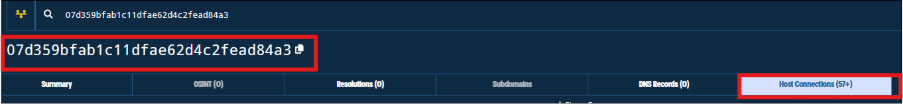

Banner Hash: 07d359bfab1c11dfae62d4c2fead84a3

Jarm Fingerprint: 2ad2ad16d2ad2ad00042d42d00042ddb04deffa1705e2edc44cae1ed24a4da

We will apply this new pivoting approach to gain deeper insight into the infrastructure we are attempting to map. By searching the banner hash within the Validin platform, we have identified 57 additional host connections potentially linked to the threat actor’s ecosystem.

Fig.6: New IPs for banner hash lookup

To expand the hunt, we will use the query in Shodan:

HTTP/1.1 404 Not Found

Content-Type: text/html

Server: IIS/7.5

Connection: close

Content-Length: 137

port:443

ssl.jarm:

2ad2ad16d2ad2ad00042d42d00042ddb04deffa1705e2edc44cae1ed24a4da

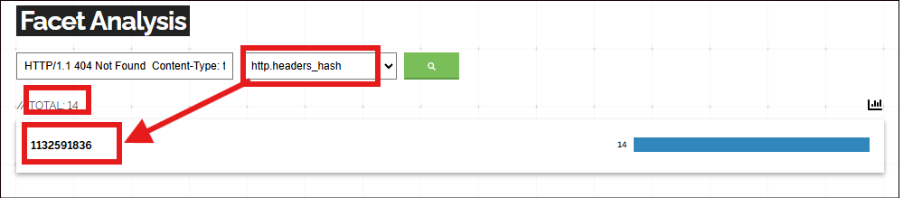

As shown in the figure below, we identified 14 IP addresses using the above query. Additionally, through facet analysis, we determined a new pivoting point: the HTTP Header Hash.

http.headers_hash:1132591836

Fig.7: Filtering using header hash

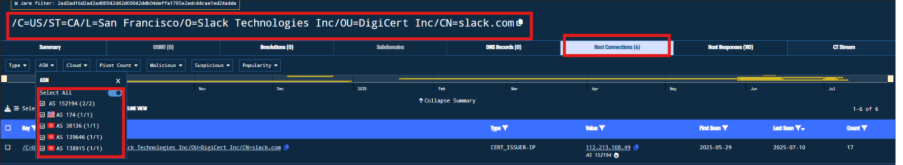

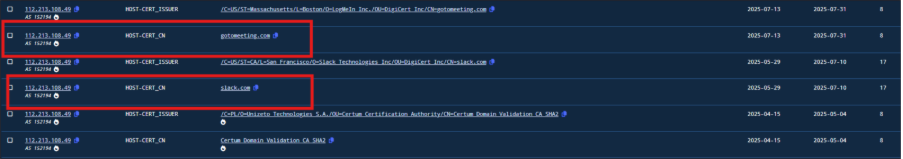

From the IP investigation, we observed that the C2 infrastructure is using SSL certificates impersonating gotomeeting.com. Additionally, during the research, another SSL certificate issuer impersonating slack.com was identified, associated with AS38136.

Fig.8: Certificates used by the threat actor

By pivoting on the SSL JARM fingerprint and certificate common name, I identified 6 additional IP addresses associated with the same or similar ASN as the issuer of the gotomeeting.com-impersonating certificate.

Fig.9: Search result based on the certificate

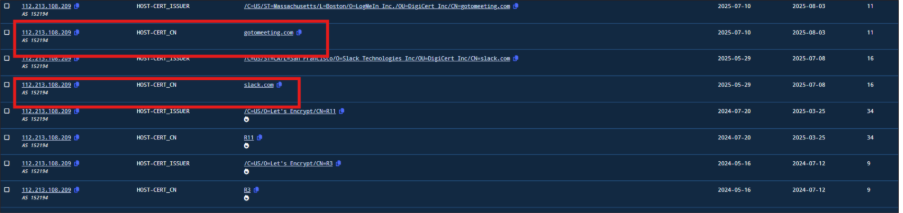

Another noteworthy observation is regarding the behavior of IP addresses 112[.]213[.]108[.]49 and 112[.]213[.]108[.]209. Initially, both were using SSL certificates impersonating slack.com, but they have recently transitioned to certificates spoofing gotomeeting.com. This is a classic example of threat actor infrastructure reuse, specifically in the form of SSL certificate switching. Such behaviour is commonly employed to maintain persistence while attempting to evade detection by threat intelligence platforms and defenders monitoring static certificate fingerprints.

Fig.10: Infrastructure Reuse

ASN Breakdown

Through infrastructure analysis, I identified top 10 Autonomous System Numbers (ASNs) associated with the threat activity. These ASNs represent hosting providers and network operators likely leveraged by the adversary for their command-and-control (C2) operations, staging servers, and other infrastructure components.

The observed ASNs include:

- AS152194

- AS149440

- AS38136

- AS138915

- AS140227

- AS54290

- AS132203

- AS20473

- AS45090

- AS200019

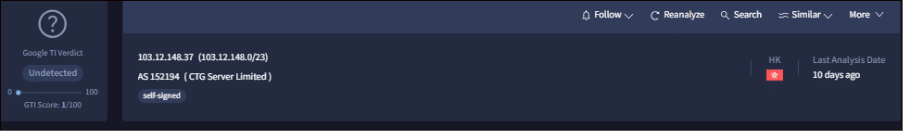

Below are three examples of IP addresses that VirusTotal vendors have not flagged as malicious. These are just a few from the total of 25 IP addresses identified during our investigation.

Fig.11: IPs not flagged by vendors in VT

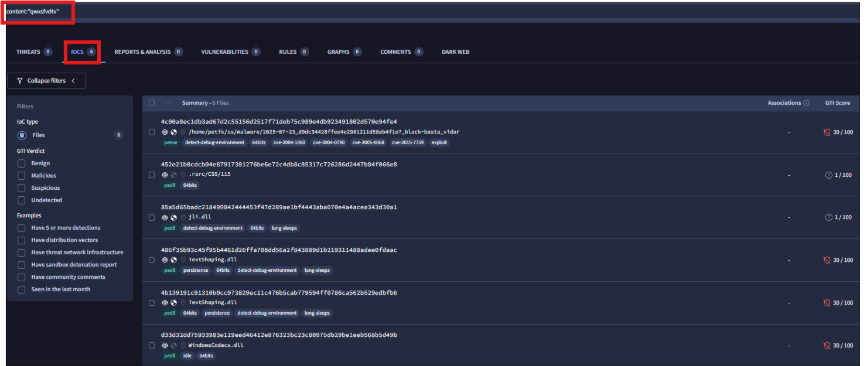

The Proofpoint article also highlights the RC4 key “qwxsfvdtv.” We used this key to pivot and uncover additional potential assets linked to the group. During a search in VirusTotal using this key, I discovered new hashes utilizing the same RC4 key.

Fig.12: RC4 key based hunt

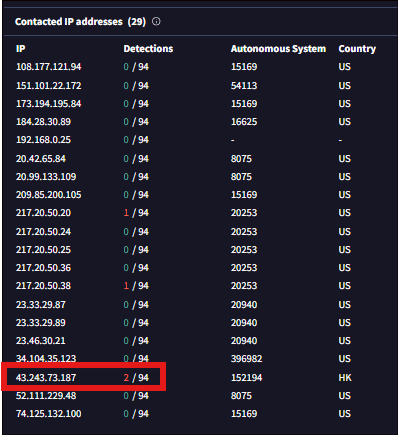

While analysing the HASH: d9dc34428ffee4e2981211d58eb4f1e7, I have found some interesting findings, in the relations tab under the contacted IPs I have observed IP: 43.243.73[.]187 which is the same IP we found during our previous hunt which is the C2 for cobalt beacon.

Fig.13: New C2’s observed

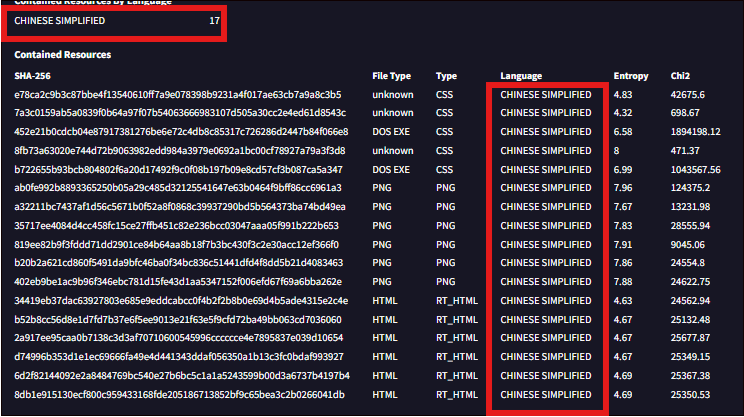

CyberProof Threat Researchers have identified the use of Chinese encryption within this Cobalt Strike instance. Based on all the findings, we can conclude that this Cobalt Strike beacon is being utilized by the same Chinese threat actor targeting Taiwan.

Fig.14: Chinese encryption within Cobalt payload

Indicators of Compromise

IP Addresses:

- 134[.]122[.]204[.]168

- 112[.]213[.]108[.]49

- 112[.]213[.]108[.]209

- 137[.]220[.]146[.]153

- 192[.]253[.]229[.]133

- 192[.]253[.]229[.]79

- 137[.]220[.]146[.]252

- 166[.]88[.]61[.]35

- 103[.]12[.]148[.]37

- 192[.]253[.]229[.]88

- 166[.]88[.]96[.]120

- 43[.]243[.]73[.]187

- 23[.]27[.]99[.]198

- 38[.]95[.]173[.]116

- 154[.]64[.]246[.]191

- 210[.]87[.]110[.]229

- 112[.]213[.]108[.]254

- 121[.]127[.]246[.]187

- 38[.]60[.]246[.]116

- 43[.]154[.]108[.]230

- 103[.]248[.]228[.]159

- 45[.]89[.]229[.]24

- 154[.]90[.]34[.]113

- 206[.]233[.]249[.]124

- 38[.]76[.]151[.]156

Domains:

- yahhiuouiyiuggkk[.]com

- yahyyigdrttyiu[.]com

- yahkkfukfikv[.]com

- coinsgame[.]vip

- lotteryasia[.]vip

SHA256:

- 4c00a8ec1db3ad67d2c55156d2517f71deb75c989e4db923491802d570e94fe4

- 452e21b0cdcb04e87917381276be6e72c4db8c85317c726286d2447b84f066e8

- 85a5d65badc218499842444453f47d289ae1bf4443aba070e4a4acea343d30a1

- 486f35b93c45f95b4461d26ffa708dd56a2f843889d1b219311488adee0fdaac

- 4b139191c91310b0cc973829ec11c476b5cab779594ff0786ca562b529edbfb6

- d33d32dd75933983e119eed46412e876323bc23c80975db29be1eeb568b5d49b

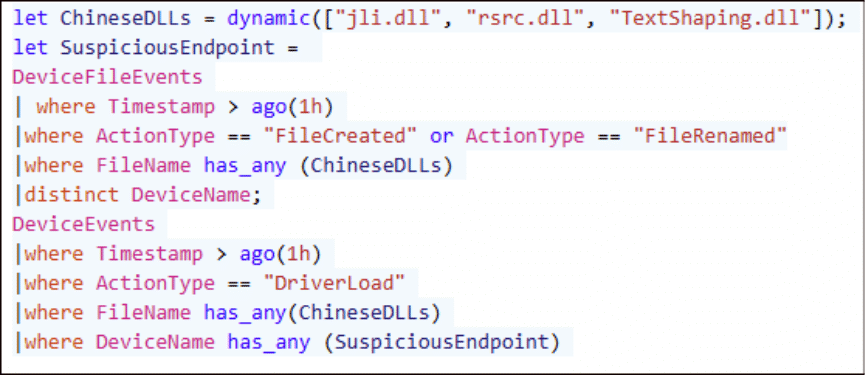

Hunting Queries

Conclusion

The investigation into the Chinese state-sponsored threat actor targeting Taiwan’s semiconductor industry reveals a sophisticated and adaptable adversary leveraging a wide range of infrastructure across multiple ASNs. Key findings include the reuse and rotation of SSL certificates impersonating legitimate services like slack.com and gotomeeting.com, dynamic IP pivoting through banner hashes and JARM fingerprints, and consistent use of Cobalt Strike as a command-and-control framework. Platforms like Shodan and Validin proved instrumental in uncovering over 25+ related IPs, with notable clustering observed around ASN

Reference: