Third party risk management (TPRM) is a security control that protects your org when vendors fail, get hacked, or change terms. Most enterprises depend on SaaS, cloud, MSPs, and API partners, so each link adds data paths and admin paths outside your direct control.

Leaders are also pushed by policy and regulation. Modern security frameworks call out supply chain cyber risk in governance, and public-company disclosure expectations raise the bar for describing cyber risk management and reporting material incidents. That includes incidents that happen on third-party systems.

In the EU, operational resilience and supply chain requirements also influence how customers evaluate vendors and how contracts are written. These obligations often shape procurement expectations, security questionnaires, and notification SLAs.

This third party risk management guide shows how to run TPRM like an operating model. It ties TPRM to first party risk management (FPRM) so you use one risk language for internal and external risk. In this article, fprm means the internal control and risk program you run day to day. It is designed for CISOs, CIOs, and SOC managers who need proof, not posture.

Why third party risk management is a board-level security control

Boards ask two questions: “What can stop revenue?” and “What can create legal duty?” Vendor risk hits both, because a cloud outage can break availability, a SaaS breach can create privacy exposure, and a supplier flaw can ship into your product.

Two trends make this board work, not optional work:

- Supply chain cyber risk is now treated as part of governance, not just procurement.

- Disclosure expectations raise scrutiny on cyber risk management and incident reporting.

A board-ready third party risk management program has clear traits:

- Risk tiers that drive effort.

- Evidence that can be audited.

- Contracts that give you rights.

- Metrics that show drift and improvement.

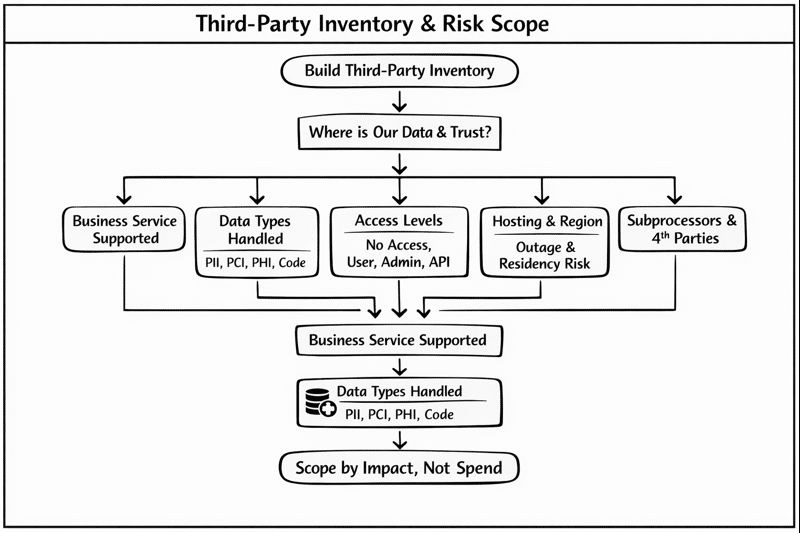

Build a defensible third-party inventory and scope

Third party risk management starts with one asset: a real vendor map. Best-practice guidance describes supplier risk as a lifecycle problem with a risk-based approach across third-party relationships.

Build an inventory that answers “where is our data and trust?” Capture these fields:

- Business service supported.

- Data types handled (PII, PCI, PHI, source code).

- Access level (no access, user, admin, network, API write).

- Hosting and region (for outage and residency risk).

- Subprocessors and key fourth parties.

- Exit risk (days to replace, data export options).

Scope with impact, not spend. If the vendor can cause material impact, it is in scope.

Also label the relationship type, because controls differ by type:

- SaaS processor: your data lives in their tenant.

- IaaS/PaaS: you share responsibility for config and logging.

- MSP/MSSP: they may have privileged access into your environment.

- Software supplier: you ingest their code, images, or libraries.

For Tier 1, document “trust boundaries” in plain terms. Note where identity is asserted, where keys are stored, and where data is replicated. This makes later incident response faster, because you already know who can revoke access and who can restore service.

Risk tiering that drives depth of due diligence

In third party risk management, tiering turns a long vendor list into a short priority list. Do not tier by spend alone. Spend is a weak proxy for cyber impact. Use inherent risk signals that match real breach paths.

Signals to score inherent vendor risk

Use a small set of signals. Keep it stable, so scoring is repeatable:

- Data risk: sensitivity, volume, and legal duty.

- Privilege risk: admin access, prod access, token minting.

- Outage risk: RTO/RPO coupling and failover options.

- Change risk: release rate, config drift, API churn.

- Chain risk: heavy subprocessing or complex open-source use.

Then define tier gates. Example tier model:

| Tier | What it means | Review cadence | Default approvals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 (Critical) | Sensitive data or admin access, or material outage impact | Quarterly | Security + Legal + Owner |

| Tier 2 (Important) | Business data, limited privilege, moderate outage impact | Semiannual | Security + Owner |

| Tier 3 (Standard) | Low data value, low privilege, easy to replace | Annual | Owner |

Now tie each tier to a minimum evidence pack:

| Tier | Minimum assurance artifacts | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 | SOC 2 Type II (or equivalent), pen test summary, IR notice SLA, DR test evidence, subprocessor list | Validate scope and exceptions. |

| Tier 2 | SOC 2 Type II or ISO 27001 cert, vuln mgmt overview, access model | Add DR proof if service is on a critical path. |

| Tier 3 | Short security attestation + data handling statement | Keep it fast. |

Supplier relationship standards also provide guidance for securing supplier relationships.

Residual risk should not equal tier. After you review evidence, adjust residual risk with “modifiers”:

- Control gaps that affect your top threats (ransomware, BEC, cloud misconfig).

- Weak notification terms that delay detection.

- Single-region design with no tested failover.

- Heavy reliance on unnamed or frequently changing subprocessors.

Compensating controls can lower residual risk. Examples include tenant-specific encryption keys, conditional access, network egress controls, and tight API scopes. Keep these controls in your FPRM register, because they live in your environment.

Evidence-based due diligence without questionnaire bloat

Questionnaires still help, but evidence should lead. Supply chain risk management guidance treats third-party cybersecurity as part of enterprise risk work, not a form fill. Regulators and governance models also describe due diligence as a lifecycle stage, tied to contract and oversight.

Use an evidence ladder. The higher you go, the more confidence you get:

- Independent assurance (SOC 2, similar reports).

- Certified ISMS scope (ISO/IEC 27001), plus supplier guidance (ISO/IEC 27036).

- Technical proof (pen tests, secure SDLC proof, log samples).

- Ops proof (IR plan, DR test notes, backup proof).

- Vendor claims (whitepapers, slide decks).

A compact artifact map helps reviewers stay consistent:

| Artifact | What it proves | Common pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| SOC 2 Type II | Tested control design and operating effectiveness over time | Scope mismatch; many exclusions; “carve-outs” for subservice orgs |

| ISO/IEC 27001 cert | ISMS exists for a defined scope | Scope may exclude the service you use |

| Pen test summary | Current exploit paths and remediation themes | No evidence of fix; tests avoid hard targets |

| DR test evidence | Restore capability and dependency mapping | Tests are tabletop only; no full failover |

| SBOM | Software component transparency | No update cadence; no linkage to vulnerability response |

| VDP process | Clear channel for vuln reporting and triage | No SLAs; no customer communication plan |

For SBOM and secure build practices, you can anchor requirements on government and industry guidance that encourages component transparency and vulnerability disclosure practices.

A short “what to check” list prevents false comfort:

- Scope: does the report cover the service you buy?

- Period: is the test window recent enough?

- Exceptions: what failed, and what is the fix date?

- Subprocessors: who else touches your data?

- Right to monitor: can you get logs and alerts?

Link third party risk management and first party risk management

TPRM gets stronger when it shares a backbone with first party risk management. If internal and external risk use different scales, leaders cannot compare tradeoffs. Governance guidance pushes integration of supply chain cyber risk into enterprise risk work.

Define FPRM as your internal control program: IAM, logging, patching, backup, and change control. Then connect TPRM to those same control goals:

To keep the link between TPRM and FPRM strong, write “control objective statements” that apply to both:

- Only approved identities can access sensitive data.

- Security logs are available to detect misuse.

- High-risk flaws are fixed within a defined window.

- Data can be restored within agreed RTO/RPO.

Then express those objectives in vendor language. For example, “audit logs must be exportable” is a vendor requirement, while “logs must reach the SIEM” is an internal FPRM requirement.

- One risk taxonomy and severity model.

- One remediation workflow and SLA.

- One set of control objectives for “must have” outcomes.

Control crosswalk for shared accountability

When you need a strict baseline, use a control catalog. Control frameworks include supply chain risk controls you can use to anchor supplier requirements.

Simple crosswalk examples:

- IAM: internal SSO/MFA + vendor SSO/MFA support and least-priv APIs.

- Logging: internal SIEM + vendor audit logs and export API.

- Vuln handling: internal SLAs + vendor patch SLAs and disclosure channel.

- Resilience: internal DR tests + vendor DR tests and region strategy.

This alignment is where “tprm” becomes measurable risk, not paperwork.

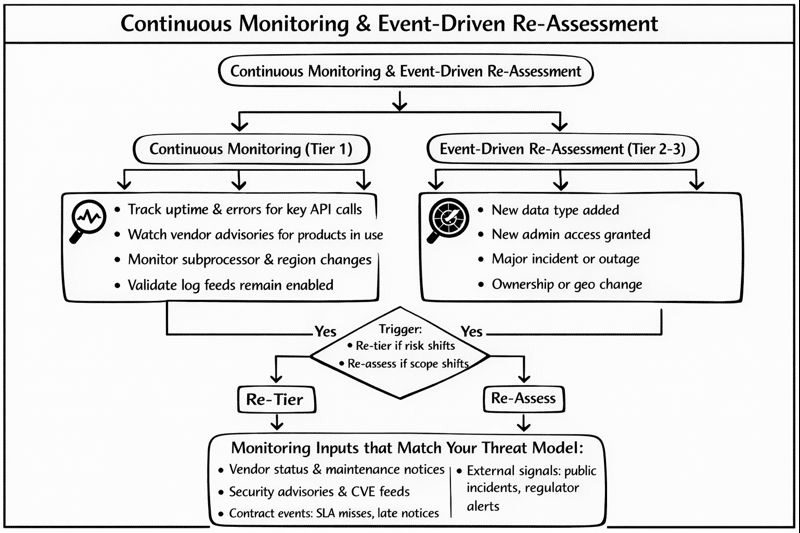

Continuous monitoring and event-driven re-assessment

Point-in-time reviews expire fast. Cloud configs change daily. Product teams add new scopes. Subprocessors shift. Supply chain guidance frames the work as an ongoing capability.

Split monitoring into two modes:

- Continuous monitoring (Tier 1).

- Track uptime and error rates for key API calls.

- Watch vendor advisories for products you run.

- Monitor subprocessor and region changes.

- Validate log feeds remain enabled and complete.

- Event-driven reassessment (Tier 2–3).

- New data type added.

- New admin access granted.

- Major incident or sustained outage.

- Ownership, geo, or service model change.

When a trigger fires, re-tier first. Then decide if the evidence pack must expand.

Pick monitoring inputs that match your threat model:

- Vendor status signals and maintenance notices.

- Security advisories and CVE feeds for products in use.

- Contract events: SLA misses, late notices, repeated audit exceptions.

- External signals: public incident notices, regulator notices, and risk updates.

Monitoring is not about scoring vendors. It is about deciding when to re-assess, escalate, or invoke contract rights.

Contract language that enforces security outcomes

TPRM lives or dies in the contract. Lifecycle guidance treats contract negotiation as a control point for ongoing oversight. Supply chain security guidance also calls for integrating cyber requirements into agreements.

For Tier 1, standardize these clauses:

- Incident notice window and required content.

- Subprocessor notice, plus approval for critical processing.

- Audit rights: assurance sharing, remediation tracking, and Q&A.

- Log access: audit logs, admin logs, and export format.

- Data rules: encryption, retention, deletion proof.

- Exit support: export, assist, and termination timelines.

If you align to supplier agreement practices, the goal is clear, shared obligations inside supplier agreements.

Security schedules and measurable SLAs for third party risk management

Put security requirements in a schedule that you can update without rewriting the whole contract. This schedule should define:

- Control objectives and evidence cadence by tier.

- Notification SLAs (initial notice, updates, and final RCA).

- RTO/RPO commitments for each critical service component.

- Data deletion timelines and proof method.

This structure supports ongoing oversight and makes audits and renewal decisions faster.

Operationalize vendor signals inside the SOC

SOC teams need vendor context at alert time. Treat Tier 1 vendors as “extended assets” in your detection work. Build playbooks, not just reports.

SOC-ready actions:

- Ingest vendor logs where available.

- Tag vendor events to business services and owners.

- Pre-build IR contacts and escalation paths.

- Define containment moves (token revoke, SSO cut, API block).

- Run joint table-top drills for high-impact vendors.

For software suppliers, add software supply chain controls. Use common requirements for SBOM availability, vulnerability disclosure, and secure software development practices.

Standardize vendor log fields for linking

When you pull logs from multiple SaaS platforms, standardize fields so linking works:

- Actor identity (user, service account, API client).

- Action type (create, read, update, delete, admin change).

- Target object (dataset, mailbox, repo, key).

- Source context (IP, device, geo, token type).

This makes it easier to write detections like “new admin + data export + token mint” across different providers.

Metrics and reporting CISOs can defend

Good third party risk management metrics drive action. They also support board oversight of supply chain cyber risk. Use the same materiality lens you use in ERM, and document your assumptions.

Third party risk management KRI dashboard template

| KRI | What it measures | Target | Owner |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 evidence freshness | % Tier 1 vendors with current assurance | ≥ 95% in 12 months | TPRM lead |

| Critical finding age | Median days open for “High” vendor gaps | ≤ 90 days | Vendor owner |

| Notice compliance | % incidents notified within SLA | ≥ 98% | IR lead |

| Log coverage | % Tier 1 vendors with logs in SIEM | ≥ 90% | SOC mgr |

| Subprocessor drift | # of Tier 1 changes without notice | 0 | Legal/Proc |

| Concentration risk | # critical services with same single provider/region | Decreasing | Arch |

Rules that keep reports honest:

- Show trend, not snapshots.

- Separate inherent vs residual risk.

- Flag repeat misses as a governance issue.

Conclusion: a pragmatic 12-month third party risk management roadmap

Build TPRM in layers, and keep it tied to FPRM. Start with basics. Then harden the Tier 1 path. Use evidence, contracts, and monitoring to reduce unknowns.

A practical 12-month plan:

- Months 0–3: inventory, tiering, and minimum evidence packs.

- Months 3–6: contract upgrades for Tier 1, especially notice and audit rights.

- Months 6–9: monitoring and re-assessment triggers; integrate with IR.

- Months 9–12: SOC playbooks, drills, and board KRIs.

If you do this well, TPRM becomes simple to run. It also becomes easy to defend.

If you operate in regulated regions, add a regulatory mapping layer. Map operational resilience and supply chain requirements to your Tier 1 baseline. It speeds up audits and aligns terms.